How Lilt Trains Machine Translation Models

In this article, you’ll find out how Lilt turns a huge pile of data and mathematical equations into natural language translations. Machine translation models can seem like magic, but here we’ll let you peek behind the scenes!

Data Collection

Training a Machine Translation (MT) model is like cooking from a recipe. You need to follow the steps, but the ingredients need to be fresh for the dish to taste good.

Lilt uses both open and paid data sources to get parallel text data, the key component to translating MT models.

Open sources are freely available and vetted sources of parallel text data, usually made available with the license CC-BY or CC-BY-SA. Some of the sources are Opus, Paracrawl, and CCMatrix.

Paid sources are those made under the CC-NC license, which makes them usable for only non-commercial and research purposes. We need to pay a fee to be able to use them in our models. An example source is WIPO COPPA V2.

When it comes to data size -- the more, the better. More data generally leads to higher quality MT models. To date we have collected 3.8B segments across 76 language pairs.

Data Preparation

Each piece of data we obtain from the above sources is rigorously processed. Suffice to say that preparation of the data is a Herculean task -- before we even start training. Here’s how we do it!

Clean and validate

We perform a basic syntax-based cleaning using the below substeps:

- Remove any blank sentences

- Remove sentences containing only punctuation

- Validate that source and target language files contain a matching number of segments (otherwise, discard the source).

Version the Data

We version our data with DVC, as it allows combining the source and target files, and any additional internal tracker files into a single unit. The single unit is a .dvc file, which is committed to our Github to track all the data sources we use.

Normalize Segments

To ensure consistency of all segments, we perform the following steps:

- Normalize Unicode: Text like unicode or HTML text is converted to human readable text. Eg Broken text… it’s flubberific! is converted to Broken text... it's flubberific!

- Normalize non-breaking spaces: For languages like French, where there are strict rules about positions of non-breaking spaces, this step adds the spaces where necessary, if they are not already present.

Filter

First, we remove potentially problematic segments from a corpus at segment- or segment-pair-level. This is known as individual filtering.

- Script: It’s a fair assumption that if a ja (Japanese) segment contains a ta (Tamil) token/phrase, it may not be usable during training. We maintain rules for scripts that are not effective when embedded in another script, and remove those segments.

- Language code: We use the python cld3 package to identify a segment’s language; if it doesn’t match the corpus language, it is discarded.

- Exclude patterns: We exclude segments matching regexes that identify problematic patterns, for example, “http://” for URLs

- Segment length: We exclude any segment longer than 300 words (configurable per language).

- Number mismatches: We exclude any segment pair which uses the same numeral system, but contains different numbers in the source and target segments.

- Length Ratio: We exclude any segments where the source or the target segments are unusually long or short for a segment pair, after comparing with a threshold computed on the entire corpus.

- Edit Distance: We exclude any segments where the source and target segments are identical or similar, since this may indicate mistranslation. We check the edit distance between the source and target segments against a minimum of 0.2.

Augment Data

When presented with unfamiliar or underrepresented data, machine translation models can fail by producing “hallucinations” -- translated text that is divorced from the original source text. To ameliorate this problem, we artificially generate (augment) examples of parallel sentences. Training with the augmented examples improves the model’s robustness and resilience towards these data, allowing us to effectively translate a wide variety of customer domains. We augment existing segment pairs in the following ways:

- Multi-segment: We concatenate up to 5 consecutive segments to form a single long segment.

- Capitalization: We capitalize the selected segments based on UPPERCASE and Title Case capitalization schemes.

- Non-Translatables: We introduce non-translatables used by our customers by detecting common tokens/phrases in source and target segments and wrapping them with ${ and } characters.

Byte-pair Encode (BPE)

The vocabulary for a large corpus can be huge, with many words seen rarely. We perform byte- pair encoding (BPE) on the words to break them down into word pieces (e.g., eating might be separated into eat and ing). This allows us to fix the size of the vocabulary, and in extension, the MT model and hence the resources required to train the model.

BPE further allows us to translate segments with tokens which haven’t appeared in the training corpora, common in morphologically rich languages such as romance and slavic languages, since we can split tokens into familiar word pieces.

Training the MT Models

Since the Transformer architecture hit the scene, we’ve based our production translation models on it.

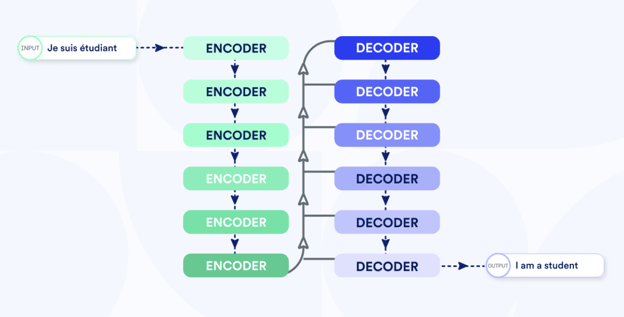

Before we move into the specifics of the transformer model, permit a quick digression on a concept known as the embedding space or continuous representation space. Each point in this high-dimensional space represents the meaning of a sentence. Two sentences that are similar in meaning will have representations that are close to each other. You can basically guess how this concept fits into designing a machine translation model. We just design two components:

Encoder: This takes a source sentence(s) and transforms it into the embedding space representation

Decoder: This takes the embedding space representation and converts it into a sentence(s) of the target language

The Encoder and Decoder together form a Machine Translation model for a given language pair. Sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) is a catchall name for the models using this encoder-decoder architecture, of which the Transformer is widely regarded as the most performant.

This is what a Transformer model looks like:

Given the architecture, we must choose the size of the model. The model size is determined by the number of parameters, and is akin to the capacity of a hotel. The information learnt from the corpora in training is analogous to the number of people actually in the hotel.

We want to achieve maximum utilization, so we use the number of sentences in the parallel corpora obtained from the Data Preparation section to determine which model size is best for a given language pair:

- Small model for when fewer parallel sentence pairs available, eg English -> Hindi

- Large model for when abundant parallel sentence pairs available, eg English -> German

Then, we train the model. The specifics could be described in a future blog post, but suffice to say we spin up lots of high-performance compute nodes, train the model with the generated training data from the Data Preparation section, and benchmark the model’s performance using test sets prepared by organizations like WMT, TED, and academic groups like LTI.

To score the models, we use automatic metrics like the BLEU score, which answers questions like “How do I objectively evaluate what is a good English to French model?”.

Having passed muster, we ship the model to our production servers, and our translators can start using it right away!